'Every night I thought I'd be killed'

Even punks hated Suicide, reacting to their gigs with astonishing violence. In response, the band locked the exits so no one could flee. Jon Wilde asks them how they survived it all,

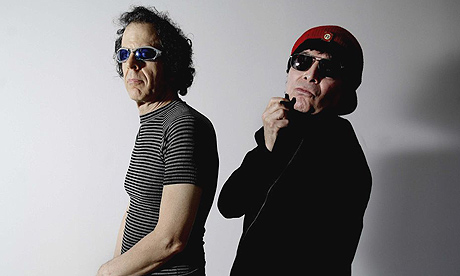

Suicide ... 'If the violence got really bad, I'd smash a bottle and start cutting my face up'. Photograph: Sarah Lee

Be it headlining Glastonbury or supporting Led Zeppelin at Knebworth, most bands that have been around for close to 40 years have one unforgettable, career-defining gig. Suicide are no exception.

"That would be the show in Glasgow in 1978 when someone threw an axe at my head," says Alan Vega with admirable matter-of-factness. "We were supporting the Clash and I guess we were too punk even for the punk crowd. They hated us. I taunted them with, 'You fuckers have to live through us to get to the main band.' That's when the axe came towards my head, missing me by a whisker. It was surreal, man. I felt like I was in a 3-D John Wayne movie. But that was nothing unusual. Every Suicide show felt like world war three in those days. Every night I thought I was going to get killed. The longer it went on, the more I'd be thinking, 'Odds are it's going to be tonight.'"

Vega, now 59, is sitting with his long-time Suicide cohort Martin Rev (age undisclosed) in the reception area of an east London branch of the Holiday Inn. Vega looks wonderfully sinister in his shades and street-fighter beret. Rev, in a distressed leather jacket and visor sunglasses, looks as if he has stepped off the set of Mad Max 2. It's fair to say that they don't blend in with the blue-rinsed sightseers and Swedish language students who mingle in the foyer.

Then again, Suicide never did blend in with anything or anybody. While this helped them become one of the most reviled bands of all time, it didn't stop them becoming one of the most influential. It's Kraftwerk who get the kudos for furthering the cause of electronic music, inspiring a generation of pop and rock bands to use synthesisers. But Suicide surely merit at least equal billing. Not only were they the blueprint for every synth-and-voice duo of the 1980s, they were equally influential on the industrial music and, quite possibly, techno scenes that followed. In a tribute album to mark Vega's 60th birthday this month, the contributors' list includes Primal Scream, Peaches, Grinderman, the Horrors, the Klaxons, Julian Cope, Vincent Gallo and even long-time Suicide fan Bruce Springsteen, who donates a live version of Dream Baby Dream.

The Brooklyn-born Alan Bermowitz (Vega) and Bronx-born Martin Reverby (Rev) first met up in 1971. Vega was engaged with sculptures and far-flung electronic experiments at the Project of Living Artists, a downtown workshop funded by the New York State Council On the Arts. Rev, already a veteran of avant-jazz ensembles, wandered into the workshop to escape the torrential rain. The two hit it off and began performing together at local galleries. Their second show was entitled Punk Music Mass, which is said to have been the first time a band used the word "punk" in an official context to describe their music. The name Suicide was inspired by Satan Suicide, an issue of Vega's favourite comic book, Ghost Rider.

When Vega and Rev started making music, they were both limited and liberated by their poverty. Often starving, living on a sandwich a day between them and unable to afford proper instruments, they made their music on the one instrument available to them: Rev's $10 Wurlitzer keyboard, over which Vega would improvise.

"For a long time, we didn't have songs as such," Vega says. "So Marty would repeatedly kick his keyboard and I'd hit the microphone stand with a broken bottle or make these horrible noises come out of a trumpet. Then I graduated to screaming, and eventually that led to writing actual lyrics."

Unsurprisingly, there were few takers for Suicide's music. "People were looking to be entertained," says Vega. "But I hated the idea of going to a concert in search of fun. Our attitude was, 'Fuck you buddy, you're getting the street right back in your face. And some.' At one of our first shows, there was a guy in the audience who'd brought this trombone. I jumped into the audience, fell over and knocked the slide out of his trombone. These South Americans took real offence to that. So they immediately attacked us with chairs, tables, anything they could get their hands on. That became the norm. I started carrying a bicycle chain on stage, figuring, if you can't beat em, join em. If the violence got really bad, what I'd do was smash a bottle and start cutting my face up. That seemed to have a calming effect on the crowd. I guess they reasoned that I was so fucking nuts that nothing they could do would bother me. I figured out a way of doing it so that I drew a lot of blood but I wouldn't be scarred for life. I had it down to a fine art. Another ploy I had was to lock the exit doors so nobody could escape. That was the ultimate 'fuck you', as far as I was concerned."

Rev is nodding thoughtfully to all this. "I was convinced we were going to be as big as the Beatles," he chips in, without irony. "All the hostility we were getting did nothing to change that. Even when the violence was going on and the blood was spilling, I'd be thinking that the crowd knew we were doing something from the future. But it wasn't a future they wanted to know about. So the antagonism got stronger and stronger. The only reaction we didn't get was being attacked by wolves. But that's only because you weren't allowed to take wolves into clubs."

By 1975, Rev had acquired a 1950s drum machine, which expanded their musical possibilities exponentially. Vega had got hold of a two-track tape recorder, which enabled Suicide to make their first demos. Meanwhile, the New York music scene was being transformed by a wave of new bands (the Ramones, Television, the Patti Smith Group, Blondie, Talking Heads) performing regularly at CBGB. One by one, those bands were signed by major record labels, while Suicide continued to be conspicuously overlooked.

It wasn't until mid-1977 that Suicide finally secured a deal, with the small French label Red Star. Their eponymous debut was released the following year. Possibly the most paranoid-sounding album ever made, Suicide's seven tracks feature Vega's spluttering rockabilly vocal fighting it out against throbbing drum machines and Rev's dissonant keyboard. The album's centrepiece is the profoundly unsettling Frankie Teardrop, about a Vietnam vet who slaughters his family.

In the US, the album was greeted by howls of disgust from reviewers. European critics, however, adored it. Sensing they'd finally found an audience ready to embrace them, Vega and Rev flew to Britain to join the Clash on tour.

"We genuinely believed that we'd get a reception fit for returning war heroes," says Vega. "But it was like going from the frying-pan to the fire. The axe in Glasgow was just one of many weapons hurled at us. When we played in Metz, someone scored a direct hit on me with a monkey wrench. I've still got the scar on my head. Supporting Elvis Costello in Brussels, we provoked a full-scale riot and the venue was stormed by police letting off tear-gas canisters. Then something very strange happened. We headlined our own tour of Britain and ended up in Edinburgh. Two songs in and there was no riot, which was very, very unusual. Then we started to see people move around. I turned to Marty and said, 'Here we go - watch out for flying objects.' To my amazement, people started dancing. I turned back to Marty and said, 'We're finished, our career is over.'"

Live 1977-1978, a limited-edition, six-CD box set featuring 13 complete live Suicide sets, gives a taste of what those gigs were like. Not every live release comes with the stark warning, "These recordings are not for the fainthearted or casual fan". The Suicide gigs were recorded on cheap, handheld cassette recorders, and it's often difficult to distinguish the sound of the band from the background noise (smashing glass and bloodthirsty heckling). Stick the CDs into your computer and, faced with a choice of genre, iTunes unhesitatingly opts for "unclassifiable". Very astute, that.

After their uncomfortable introduction to Europe, Vega and Rev spent time in limbo. "Malcolm McLaren offered to manage us but he wanted to turn us into a disco outfit, so we politely declined," Rev says. Instead, they delivered a second album, also entitled Suicide, produced by Ric Ocasek of the Cars. A more polished affair, it sold in shockingly small numbers.

Vega and Rev went their separate ways. Astonishingly, for a brief period in the early 1980s Vega became a pop star in France, and won himself a deal with a major label that unsuccessfully attempted to market him as an alternative Bruce Springsteen. He has since continued to release solo albums, the latest being 2008's Station, and has supported himself by selling his sculptures, "mostly to rich Texans who don't realise there's usually a good old New York cockroach stuck on the bottom". Rev, meanwhile, has eked out an even more precarious living by releasing the occasional solo album, producing small-time bands, or playing sessions with obscure electronic outfits.

From time to time, Vega and Rev have reunited for a Suicide tour or album. You sense they miss the days when dodging axes and monkey wrenches was simply part of the job.

"I guess we're a historical act now," asks Vega. "We've turned into fucking entertainers. It was never meant to turn out that way. But what can you do? People are completely unshockable now. Even if you brought a fresh corpse out on stage and started eating it with a fork, no one would bat an eyelid. Still, one of the things about playing live these days is that at least we know we're not going to die on stage. That's kinda nice, man."

"That would be the show in Glasgow in 1978 when someone threw an axe at my head," says Alan Vega with admirable matter-of-factness. "We were supporting the Clash and I guess we were too punk even for the punk crowd. They hated us. I taunted them with, 'You fuckers have to live through us to get to the main band.' That's when the axe came towards my head, missing me by a whisker. It was surreal, man. I felt like I was in a 3-D John Wayne movie. But that was nothing unusual. Every Suicide show felt like world war three in those days. Every night I thought I was going to get killed. The longer it went on, the more I'd be thinking, 'Odds are it's going to be tonight.'"

Vega, now 59, is sitting with his long-time Suicide cohort Martin Rev (age undisclosed) in the reception area of an east London branch of the Holiday Inn. Vega looks wonderfully sinister in his shades and street-fighter beret. Rev, in a distressed leather jacket and visor sunglasses, looks as if he has stepped off the set of Mad Max 2. It's fair to say that they don't blend in with the blue-rinsed sightseers and Swedish language students who mingle in the foyer.

Then again, Suicide never did blend in with anything or anybody. While this helped them become one of the most reviled bands of all time, it didn't stop them becoming one of the most influential. It's Kraftwerk who get the kudos for furthering the cause of electronic music, inspiring a generation of pop and rock bands to use synthesisers. But Suicide surely merit at least equal billing. Not only were they the blueprint for every synth-and-voice duo of the 1980s, they were equally influential on the industrial music and, quite possibly, techno scenes that followed. In a tribute album to mark Vega's 60th birthday this month, the contributors' list includes Primal Scream, Peaches, Grinderman, the Horrors, the Klaxons, Julian Cope, Vincent Gallo and even long-time Suicide fan Bruce Springsteen, who donates a live version of Dream Baby Dream.

The Brooklyn-born Alan Bermowitz (Vega) and Bronx-born Martin Reverby (Rev) first met up in 1971. Vega was engaged with sculptures and far-flung electronic experiments at the Project of Living Artists, a downtown workshop funded by the New York State Council On the Arts. Rev, already a veteran of avant-jazz ensembles, wandered into the workshop to escape the torrential rain. The two hit it off and began performing together at local galleries. Their second show was entitled Punk Music Mass, which is said to have been the first time a band used the word "punk" in an official context to describe their music. The name Suicide was inspired by Satan Suicide, an issue of Vega's favourite comic book, Ghost Rider.

When Vega and Rev started making music, they were both limited and liberated by their poverty. Often starving, living on a sandwich a day between them and unable to afford proper instruments, they made their music on the one instrument available to them: Rev's $10 Wurlitzer keyboard, over which Vega would improvise.

"For a long time, we didn't have songs as such," Vega says. "So Marty would repeatedly kick his keyboard and I'd hit the microphone stand with a broken bottle or make these horrible noises come out of a trumpet. Then I graduated to screaming, and eventually that led to writing actual lyrics."

Unsurprisingly, there were few takers for Suicide's music. "People were looking to be entertained," says Vega. "But I hated the idea of going to a concert in search of fun. Our attitude was, 'Fuck you buddy, you're getting the street right back in your face. And some.' At one of our first shows, there was a guy in the audience who'd brought this trombone. I jumped into the audience, fell over and knocked the slide out of his trombone. These South Americans took real offence to that. So they immediately attacked us with chairs, tables, anything they could get their hands on. That became the norm. I started carrying a bicycle chain on stage, figuring, if you can't beat em, join em. If the violence got really bad, what I'd do was smash a bottle and start cutting my face up. That seemed to have a calming effect on the crowd. I guess they reasoned that I was so fucking nuts that nothing they could do would bother me. I figured out a way of doing it so that I drew a lot of blood but I wouldn't be scarred for life. I had it down to a fine art. Another ploy I had was to lock the exit doors so nobody could escape. That was the ultimate 'fuck you', as far as I was concerned."

Rev is nodding thoughtfully to all this. "I was convinced we were going to be as big as the Beatles," he chips in, without irony. "All the hostility we were getting did nothing to change that. Even when the violence was going on and the blood was spilling, I'd be thinking that the crowd knew we were doing something from the future. But it wasn't a future they wanted to know about. So the antagonism got stronger and stronger. The only reaction we didn't get was being attacked by wolves. But that's only because you weren't allowed to take wolves into clubs."

By 1975, Rev had acquired a 1950s drum machine, which expanded their musical possibilities exponentially. Vega had got hold of a two-track tape recorder, which enabled Suicide to make their first demos. Meanwhile, the New York music scene was being transformed by a wave of new bands (the Ramones, Television, the Patti Smith Group, Blondie, Talking Heads) performing regularly at CBGB. One by one, those bands were signed by major record labels, while Suicide continued to be conspicuously overlooked.

It wasn't until mid-1977 that Suicide finally secured a deal, with the small French label Red Star. Their eponymous debut was released the following year. Possibly the most paranoid-sounding album ever made, Suicide's seven tracks feature Vega's spluttering rockabilly vocal fighting it out against throbbing drum machines and Rev's dissonant keyboard. The album's centrepiece is the profoundly unsettling Frankie Teardrop, about a Vietnam vet who slaughters his family.

In the US, the album was greeted by howls of disgust from reviewers. European critics, however, adored it. Sensing they'd finally found an audience ready to embrace them, Vega and Rev flew to Britain to join the Clash on tour.

"We genuinely believed that we'd get a reception fit for returning war heroes," says Vega. "But it was like going from the frying-pan to the fire. The axe in Glasgow was just one of many weapons hurled at us. When we played in Metz, someone scored a direct hit on me with a monkey wrench. I've still got the scar on my head. Supporting Elvis Costello in Brussels, we provoked a full-scale riot and the venue was stormed by police letting off tear-gas canisters. Then something very strange happened. We headlined our own tour of Britain and ended up in Edinburgh. Two songs in and there was no riot, which was very, very unusual. Then we started to see people move around. I turned to Marty and said, 'Here we go - watch out for flying objects.' To my amazement, people started dancing. I turned back to Marty and said, 'We're finished, our career is over.'"

Live 1977-1978, a limited-edition, six-CD box set featuring 13 complete live Suicide sets, gives a taste of what those gigs were like. Not every live release comes with the stark warning, "These recordings are not for the fainthearted or casual fan". The Suicide gigs were recorded on cheap, handheld cassette recorders, and it's often difficult to distinguish the sound of the band from the background noise (smashing glass and bloodthirsty heckling). Stick the CDs into your computer and, faced with a choice of genre, iTunes unhesitatingly opts for "unclassifiable". Very astute, that.

After their uncomfortable introduction to Europe, Vega and Rev spent time in limbo. "Malcolm McLaren offered to manage us but he wanted to turn us into a disco outfit, so we politely declined," Rev says. Instead, they delivered a second album, also entitled Suicide, produced by Ric Ocasek of the Cars. A more polished affair, it sold in shockingly small numbers.

Vega and Rev went their separate ways. Astonishingly, for a brief period in the early 1980s Vega became a pop star in France, and won himself a deal with a major label that unsuccessfully attempted to market him as an alternative Bruce Springsteen. He has since continued to release solo albums, the latest being 2008's Station, and has supported himself by selling his sculptures, "mostly to rich Texans who don't realise there's usually a good old New York cockroach stuck on the bottom". Rev, meanwhile, has eked out an even more precarious living by releasing the occasional solo album, producing small-time bands, or playing sessions with obscure electronic outfits.

From time to time, Vega and Rev have reunited for a Suicide tour or album. You sense they miss the days when dodging axes and monkey wrenches was simply part of the job.

"I guess we're a historical act now," asks Vega. "We've turned into fucking entertainers. It was never meant to turn out that way. But what can you do? People are completely unshockable now. Even if you brought a fresh corpse out on stage and started eating it with a fork, no one would bat an eyelid. Still, one of the things about playing live these days is that at least we know we're not going to die on stage. That's kinda nice, man."

No comments:

Post a Comment