Jeff Tweedy: why the album still matters

The Wilco man’s latest offering, Sukierae, is a double vinyl album by design. He explains how the format shaped his aesthetic and set him on an ‘inevitable path’

Whenever the so-called experts say the album is dying as a format, I think: “Since when have we listened to so-called experts?” Are video games killing chess as well?

I’ve just made a double album, Sukierae, which has two distinct discs. I understand in this day and age there might not be many people who will listen to it that way, but it doesn’t matter – because I want to listen that way. I’m not a curmudgeon, a luddite or anti-modern technology doomsayer. I just want to listen to the album and have a feeling that one part ,has ended, and now I can take a little breather before I listen to the second part. Or I can listen to the second part another time. It’s a double record on vinyl, so there are three breaks like that. I wanted it to have different identities artistically and the album format allows me to do that.

An album is a journey. It has several changes of mood and gear. It invites you into its environment and tells a story. I enjoy albums, and I assume that if I enjoy them there must be others who feel the same.

I don’t remember ever not having albums. My youngest brother is 10 years older than me, and my sister is 15 years older, with another brother in between them. When I was a kid, they had moved out already, so I inherited their Monkees, Herman’s Hermits and Bob Dylan albums long before I remember ever buying any. They completely changed my life and set me on a path that was unavoidable, in the sense that I was given little choice.

If I go back and think about the albums and records that were in my house, a lot of them still shape what I do. My father had a record of old steam locomotive sounds and I still think about that all the time: the idea that you can sit and listen to anything and have a stimulating experience, just sitting and being bombarded by sound.

‘If you’ve got a 12-inch album with a picture of somebody’s head on it, it’s the same size as your head. You can sit it up and talk to it. Not that I’ve ever done that’

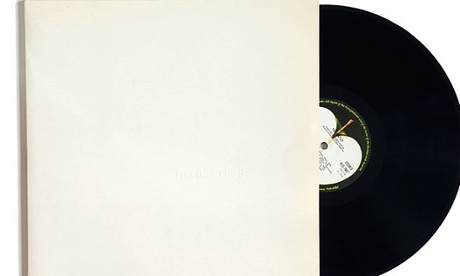

I could make an equally forceful argument for the Beatles’ White Album. For me, as a child, that was the ideal situation: this collective of people who were not being held in the confines of a genre – a word I didn’t know at the time. It was really obvious that there was something much broader than the Monkees there (at that point I didn’t have those records where the Monkees were trying to be the later Beatles).

We weren’t a rich family, so I had a lot of compilations and less successful records by people, the ones you could get more cheaply. Between the Buttons by the Rolling Stones wasn’t the biggest record and it’s unpredictable – a hodgepodge – but it’s a great record that still inspires me. And as I’ve grown older I really appreciate those records that sound like they have a singular mission.

For example, the first album by Suicide came at me fully formed. You’d think: “How did somebody do that?” Even now, 30 or 40 years down the road, it sounds like a completely steadfast, undying commitment to an aesthetic. You can’t leave the room while that record plays, and you come out of it scarred for life. If you listen to Frankie Teardrop even once, you’re not going to be as happy as you were.

I still listen to whole albums and play them over and over. When I think about records that really hit me as a kid, I realise that’s why it’s hard for me to stay focused on one thing; that’s why Wilco have made so many wildly different records. I’ve never been able to adhere to one sonic mission statement, although I love albums that do. Wire’s Pink Flag is like that, the first Ramones record or the Stooges’ Fun House. If you’re in the mood to be in those worlds, they are incredible to listen to from beginning to end.

The decline of the album began with the advent of the CD. The maximum amount of music on a vinyl album is 50 minutes over two sides. The CD format is much longer. I don’t think there are many pieces of music – my own records included – that can sustain interest over 40 minutes without a break, and leaping around from idea to idea for that amount of time gets exhausting.

CD artwork also reduced the album’s impact. If you’ve got a 12-inch album with a picture of somebody’s head on it, it’s the same size as your head. You can sit it up and talk to it. Not that I’ve ever done that; really, I’ve really never done that! But the White Album artwork is incredible. Having a white square in your room looks like there’s some piece of your world missing, that’s only really being filled by this music.

‘The album format matters, because it matters to me and I don’t think I’m particularly unique or special. If it means a lot to me, then it must matter to someone else as well’

Working toward Sukierae I must have written or recorded around 90 songs. I was pretty sold on the idea of two really good-sounding vinyl sides, but no matter how we tried to sequence the songs, we kept getting halfway into another record. Then, in the last couple of weeks of recording, I had this burst and recorded five new songs, which all started to feel like part of a whole other record. So, we sequenced it as disc one and disc two. The album gets simpler and softer and bolder at the same time. The idea is that as it winds down it gets clearer.

The record has several marked gear shifts, allowed by the double album format. Nobody Dies Anymore is a childish daydream about things being here for ever, partly inspired by something my son said after 9/11: “If everybody didn’t die then bad people would live forever and eventually there would be a lot of bad people all existing at once.” Low Key is autobiographical: “I don’t jump for joy. If I get excited, nobody knows.” I think about that all the time when I’m onstage. That if an audience seems a little bit lacklustre it’s because it’s full of people more like me, rather than people going fucking bananas because I would never do that. If I could be transported to some of the greatest concerts of all time I would still sit there scratching my chin, even though inside I would be ecstatic.

These are key tracks but deliberately placed to be heard in the middle of the album. Listening to it all at once is a leap of faith, but I know that the idea of listening to a work all the way through and being taken along for the whole ride is becoming antiquated for a lot of people.

Nowadays, people download tracks. When I was a kid we’d make tapes, samplers for your friends. Most often it was a way into the whole record, a gateway drug. But both my sons still listen to records. They have turntables in their rooms and really good record collections. They’re weirdos, not typical, but they do have friends that share those interests.

So does the album format matter? In one sense, I don’t know if it does. The crucial thing is that people keep making art. I just think the world’s a better place when people make stuff not to make a million dollars or to make them famous, but just to be creative. On the other hand, the album format matters, because it matters to me and I don’t think I’m particularly unique or special. If it means a lot to me, then it must matter to someone else as well, and if that’s the vocabulary or language we have to speak to each other, that’s to be honoured and that’s beautiful. There’s no reason to question it.

No comments:

Post a Comment